The word “strategy” is a confusing mess.

Every day I overhear someone asking “Hey, what’s our strategy for dinner tonight?” or “Wow! What an awesome strategy!” referring to some trick to pick up their dog’s 💩 from the sidewalk¹.

At the same time, I also hear people proclaim that strategy doesn’t matter – that execution is the only thing that matters.

And while I agree that execution is essential to winning, discarding strategy altogether usually means that we’re not paying enough attention to why we’re doing what we’re doing and why we’ve prioritized things the way we have.

In this post, I’m going cover 5 problems with the word strategy which explain why there’s so much confusion about the concept. Most importantly, understanding strategy better gives us a huge leg up in our competitive landscape.

Problem 1: The word Strategy has a huge burden to carry

The first problem with the word strategy is that it has a huge burden to carry.

In English, the word strategy is truly unique. There is no other word that means the same thing as the word strategy.

The phrases “plan of action” or “master plan” seem to get closest, but still fall way short since strategy is so much more than just a plan or a todo list.

Strategy is an important concept with so much nuance. Strategy involves:

- choosing our objectives

- evaluating the resources at our disposal

- understanding the competitive landscape

- attempting to predict what our opponents and allies might do

- trying to understand the tradeoffs between all of the possible actions we could take in any given moment

- and finally choosing what to actually do

Only after we figure all of that out does execution really enter the picture. And even then we can’t just myopically focus on execution. Our strategies must also be dynamic as we implement them and receive new information.

And since there’s no other word that encapsulates all of this meaning, the only word we have – strategy – must carry this huge burden.

That’s why it’s so important to properly define strategy. Which brings us to the second problem with the word strategy: There is no clear definition.

Problem 2: There is no clear definition of Strategy

Not only is strategy a unique word with a big burden to carry, there’s also no clear definition. I’ve spent dozens of hours searching for a good off-the-shelf definition and I’ve never found one – not in the dictionary, not online, not in all of the corporate strategy books I’ve read, and not in the academic business literature from reputable sources like Harvard Business Review.

Even in the most cited and famous article on strategy – titled “What is Strategy?” By Michael Porter – the word is never defined. Three times Porter rhetorically asks himself what strategy is and three times he given a different description.

10 years ago I started studying entrepreneurship and strategy at Stanford for my master’s degree. I recently reviewed my notes from my strategy courses and not once did we even attempt to define the word Strategy. Why? Because it’s really hard.

And one of the biggest reasons strategy is a hard word to define is because the word has at least two distinct meanings.

Problem 3: Strategy is both a process and an outcome

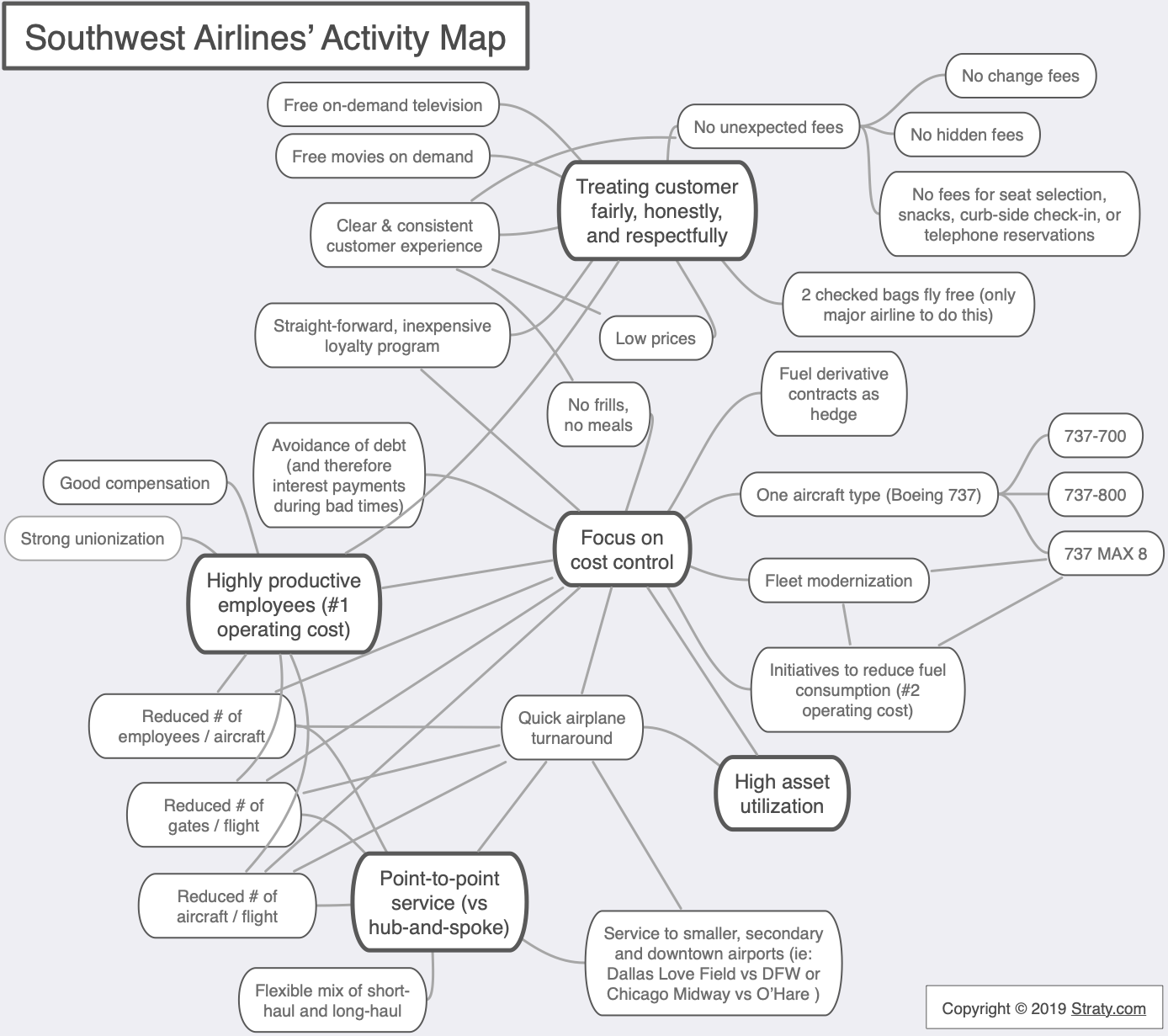

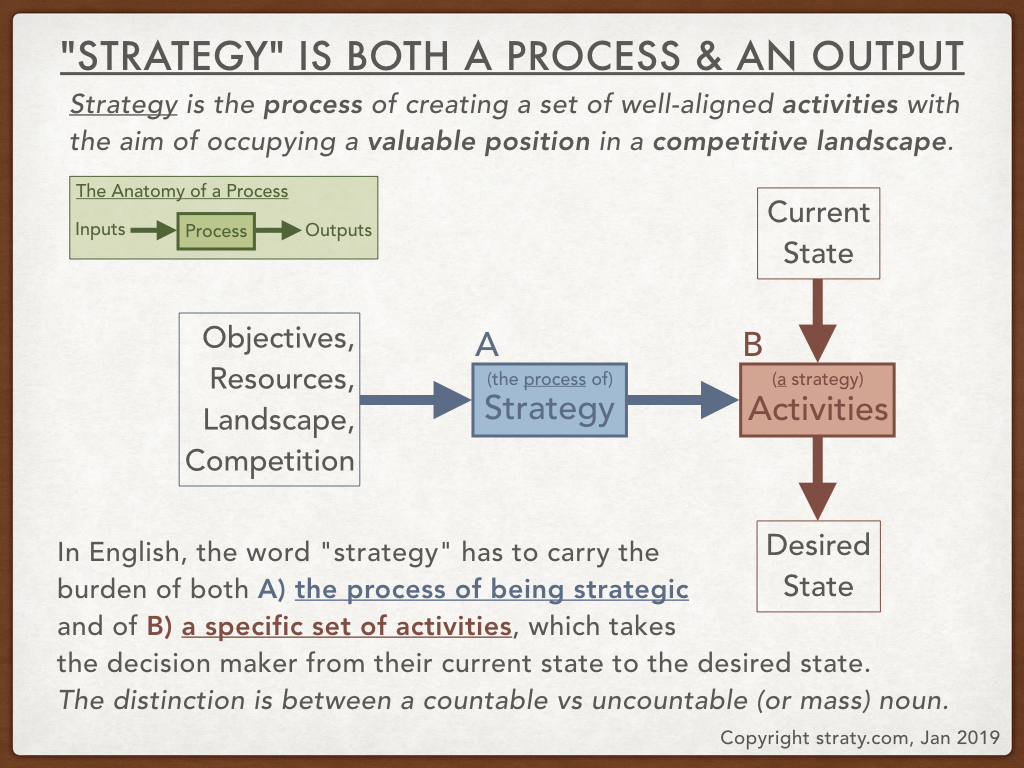

Even without defining strategy, you can see that there are two – related but different – meanings of the word strategy. The first meaning represents the concept of strategy. The second meaning represents a particular strategy.

I like to illustrate this point by using both meanings in the same sentence:

Before the weekend retreat, the executives didn’t even understand the difference between strategy and tactics, but afterwards they were ready to present two strategies to the board.”

You can see that the first usage is about the concept of strategy – in contrast to the concept of tactics. The second usage is about the two specific strategies the executives developed.

For the linguist nerds out there: The difference here is between a countable noun and uncountable noun – also called mass noun. In English, a noun is countable if you can slap a number in front of it and it still makes sense. “There are six chairs in the dining room.” vs “There are six furnitures in the dining room.” 🤔. Chair is countable. Furniture is not. Also, countable nouns take the modifier ‘fewer’ and uncountable nouns take ‘less.’ “We need fewer chairs in the dining room!”

Some nouns – like strategy – have both a countable form and an uncountable form… which can be confusing.

Back in January, I developed a slide to illustrate this idea.

Long story short: strategy can mean:

- the process of being strategic, of strategizing, or the field of strategy as a whole

- the output of that process – a strategy that you can choose to implement or not

The problem here is obvious: there are 2 distinct meanings for the exact same word.

Problem 4: Tactics are often mistaken to be strategy

The fourth problem with the word strategy is that: Tactics are often mistaken as strategy. This confusion is particularly disastrous for inexperienced strategists.

When we understand the difference between strategy and tactics, we can avoid the latest engineering/marketing/sales/investment/etc fads which are almost always tactics, not strategies. Tactics should always serve our broader strategy – not the other way around.

So while Virtual Reality advertising on YouTube may be the hottest new marketing fad, if it’s not aligned with our over-arching marketing strategy, then it’s a distraction and a waste of resources.

Which brings me to the 5th, and final, problem with the word strategy: When we don’t understand what strategy is, others will take advantage of us.

Problem 5: Business gurus and consultants benefit at our expense when we don’t understand strategy

I’m all for hiring experts, for getting coaching or mentorship when we need help achieving a goal or objective. But too often individuals and businesses are counting on some third party to copy-paste a solution that worked for someone else in an attempt to fix their particular problem.

When we understand what strategy is and isn’t – when we’ve developed a strategy tailored to our objectives, our resources, and our competitive landscape – then it’s usually much more obvious what outside help we need to achieve our goal.

When we don’t fully understand one or all of these components of strategy, handing our money over to some guru to solve all of our problems can be really attractive.

Wrapping It Up

Alright, the 5 problems with the word strategy are:

- The word Strategy has a huge burden to carry.

- There is no clear definition of Strategy.

- Strategy is both a process and an outcome.

- Tactics are often mistaken to be strategy.

- Business gurus and consultants benefit at our expense when we don’t understand strategy.

I’ve addressed many of these problems by defining strategy (both the process and the output) and by distinguishing strategy from tactics.

¹ Invert the bag, wear it like a glove, pick up 💩, re-invert, tie a knot, and throw away (or, if you live in SF, just leave the bag anywhere you like when no one is looking).